Strategy: Timey Recommendations

Timey was an in-house product that was supposed to elevate Start Studio to SaaS-company status. We worked on it for 6 years, but eventually stopped even using it ourselves. I reviewed Timey and presented these findings about what went wrong, and how to change it.

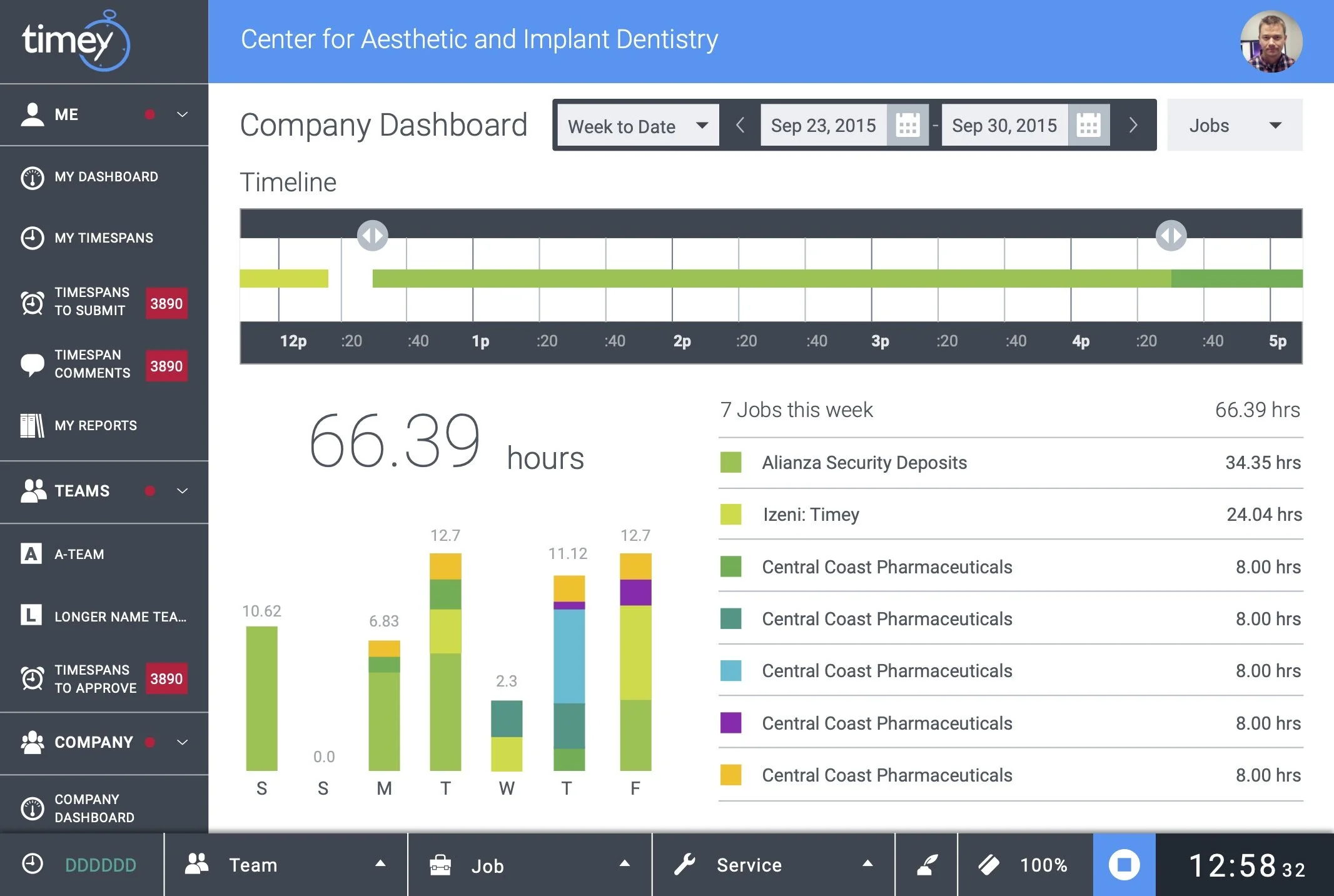

The Timey dashboard, showing a theoretical week’s worth of work.

Timey Recommendations

Timey is an in-house Start Studio product — a time and attendance tracker that was meant to take us from agency to SaaS company. Agency status, in fact, was just to bootstrap Timey. It was one of my first projects at Start Studio, and I worked on it, off and on, for six years. We developed it enough to use in-house. However, we failed to bring it to market, and, after a few years, we abandoned its use altogether in favor of Harvest, a competitor’s product, to track our own time. When our CEO decided to resurrect Timey, I did a thorough review, with the following findings and recommendations, including following the approach from Nail It Then Scale It (NISI) by Nathan Furr and Paul Ahlstrom.

Timey is a failed product, because we’ve taken a failed approach. We need to do a 180.

Intro

Of the many products we’ve built over the past 10 years, Timey may be the worst. It was so bad that not only could we not bring it to market — we even stopped using it ourselves. After 6 years (6 years!) of design and development, we now pay a competitor to use their time-tracking service.

I was really frustrated when we dropped Timey for Harvest. I had taken ownership of this project, and this felt like the final nail in the coffin, burying several years of work with nothing to show for it. But, with some distance, I now think the switch to Harvest was one of the best moves we could have made in regards to Timey. It gave me a fresh perspective, which allowed me recognize some problems that contributed to Timey’s failure.

In our defense, when we started Timey, we really didn’t know what we were doing. We spent a lot of time and money, and built some cool stuff — that didn’t go anywhere. We had no consistent approach for gathering objective data and overcoming innate bias. We had no tool to validate features and determine if we were on the right track. So Timey landed in perpetual product limbo, floating aimlessly in a fog of unfounded assumptions until it vanished almost entirely.

We’ve been doing it wrong for a long time, and we have some deeply-ingrained habits. Insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results. If we want to turn Timey around, it will require a 180° change in our approach.

The good news is that in NISI we have the tools to help us overcome our limiting factors: biases, assumptions, and ignorance.

This requires making customers an essential part of our process: gathering feedback, so we can create something that solves a monetizable pain.

This requires approaching Timey with a critical eye, focusing our limited resources on the features that will provide the biggest return on our investment — to the exclusion of all else. It means being willing to pivot if we discover a new, promising direction; or to scrap the project entirely if there’s no clear path to success.

This requires regular backchecks from respected outside points of view: consultants or mentors who can provide a reality check, and validate (or invalidate) our conclusions.

I recommend these 4 steps as our new approach, both with the product as a whole, and with individual features:

Approved: Customer-approved, that is — it addresses a specific, validated customer pain.

Focused: We approach design and development with laser-like focus on simple solutions that address the pain, to the exclusion of everything else.

Tested: Customers try it out and provide feedback. Then we iterate and test again as needed.

Checked: Mentors review and respond to our conclusions, correcting bias and keeping us on track.

1. Approved

From a NISI standpoint, our approach to Timey has been completely backward. We spent lots of time and money to build a product we didn’t know if people would buy. Because Timey is entering a saturated market, we need customer input to determine how we might differentiate our product so it can succeed in this saturated space.

The key is: we are not the customer. I’m going to repeat that in bold caps, because it’s important enough to override good typographic conventions: WE ARE NOT THE CUSTOMER! Our whole approach to Timey was based on the assumption that we represented our typical customer. We don’t. The only way to understand the customer is to get feedback from them. Otherwise we’re left with just our assumptions, and we can see how that’s worked out.

Additional assumptions that crippled Old Timey from a customer-approval standpoint:

All features are created equal, and therefore more features = more value — instead of finding out from potential customers what they most valued, and prioritizing accordingly.

If something is easy to implement, we should just do it — instead of prioritizing features based on customer input, and focusing only on what’s most important.

In Old Timey we solved a lot of hard problems that we didn’t need to solve — a timeline graph with adjustable timespan bars, for example. We failed to first identify problems that were essential to solve.

Feedback from potential customers allows us create the product Timey needs to be, as opposed to the product we think it should be. Not that we allow customers to dictate priorities — we determine essential features as we collect and synthesize customer feedback. Other features, even though they have value, must be postponed in favor of the essential.

2. Focused

Old Timey was overly complex. This is normal. People always start with complexity. And what’s so bad about complexity? After all, some things need to be complex. But defaulting to complexity instead of striving for simplicity bogs down the whole process, from design, to development, to testing, to maintenance. I call this complexity bias. Steve Jobs said, “Simple can be harder than complex. You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple.”

The following assumptions plagued Old Timey by over-complicating it:

Timespans must be tied to the clock — instead of simply being a timer.

Timey must prevent employees taking advantage of their employers — instead of simply providing a mechanism for tracking time, and allowing employers to address personnel issues as they arise.

Timey must facilitate all time-tracking-related communication — instead of allowing that to take place in established channels outside of Timey.

Here are some other Old Timey examples of complexity bias:

Jobs and services nested to four levels deep. That requirement caused a lot of headaches, but it’s not necessary to track time.

Scoping jobs an employee can access by teams they’re on, and services by roles they have. Employees had to track down an admin to get access to a job or service they needed, instead of just being able to work. The admin had to stop what they were doing, and go into Timey to add that person to a team or a role (sometimes both), instead of just being able to work. Timey was interrupting work, not facilitating it. And our solution to this problem, having employees request access to jobs and services within the app, complicated things even further.

How about having a billable percentage for everything? Employees, jobs, services — even individual timespans. A single timespan could have four different billable percentages to sort through. How complicated can you get?

There were reasons for all of these decisions, but, in the long run, they hurt our product and prevented its launch. We need to recognize complexity bias, and work to simplify, for our users, our devs, and our bottom line.

Staying focused on providing simple solutions to necessary problems also helps get a product to testing quickly.

3. Tested

Even after we think we’ve heard and understood customer pain, testing our solutions with potential customers reveals unexpected results. Maybe we didn’t really understand the pain, or we haven’t yet nailed the solution. We need that feedback to make sure we’re on the right track.

Of course, we don’t allow customers to dictate priorities. They provide valuable input, but we process the information, and make final decisions as to what would be best. This was a challenge when we only had one beta-tester (that German car repair place). When there was only one voice requesting features, it held oversized sway. We allowed them to dictate some idiosyncratic features that introduced security risks (allowing multiple people to be clocked in at once on the same browser tab), even though they benefited one company and the unique way they did things.

This is why customer testing, whether on a prototype or beta-testing, should involve multiple points of view. The Nielsen Norman Group found that, for usability testing, 5 is an ideal number of test subjects. This is realistic and doable.

The end of testing is assessing data. Once we’ve gathered that valuable test data, we need to be sure we interpret it as objectively as possible.

4. Checked

Our innate biases lead us to interpret feedback in ways that we want to hear. Recognizing our biases and assumptions requires courage and intellectual honesty. But those qualities alone aren’t enough, because they involve subjective evaluation of our own objectivity. I suggest a two-fold approach to guard against this:

First, we record or transcribe all feedback and research. That way, we can come back to it later with a fresh perspective, to see if our original impression was on target.

Second, we put in place a system of backchecks from outside points of view: 3 trusted business consultants/mentors (possibly former clients) — people who embrace the NISI philosophy, and can expose bias and assumptions we don’t recognize on our own.

These measures will provide an added degree of objectivity — a reality check against innate bias that may lead us to misinterpret the feedback we get from customers, and take Timey in the direction we think it should go, rather than the direction our customers need it to go.

Conclusion

Timey is a failed product, the result of a failed approach. We can do a 180, using NISI to create a product that is:

Approved

Focused

Tested

Checked

Through this approach, we can address the fundamental problems that relegated Old Timey to perpetual product limbo. We can identify a niche, even in a saturated market, where Timey can thrive — or we can determine that it can’t thrive, and make a clean break. Either way, we can move forward with confidence, focusing our limited resources where they’ll have the most impact.